Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

Advertisement

Scientific Reports volume 15, Article number: 27678 (2025)

1815

1

Metrics details

This article has been updated

This paper presents the design and simulation of an optimized fuzzy logic Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) controller for grid-tied wind turbines, utilizing Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithm (GA). Four distinct methodologies are explored to determine the most suitable approach. Initially, the conventional perturb-and-observe technique is employed. Subsequently, the efficacy of fuzzy logic control without optimization is evaluated. Following this, FLC is enhanced by integrating particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithms. The novelty of employing fuzzy logic control optimized with PSO and GA lies in its ability to address inherent challenges in wind energy systems, such as varying wind speeds and grid voltage fluctuations. By combining the adaptability of fuzzy logic with the optimization systems of PSO and GA, our approach maximizes energy yield, ensures grid stability, and enhances overall system performance. This methodology represents a significant stride in renewable energy integration and grid management. To expedite the tuning process, the input and output membership function mappings are quickly adjusted to achieve the desired set point. Moreover, the mitigation of undesired occurrences such as distortion and abrupt wind speed variations is carefully reduced. A comparative analysis is provided between conventional P&O, standalone FLC, FLC-GA, and FLC-PSO to improve the wind energy conversion system. PSO and GA are capable of optimizing a fuzzy logic MPPT controller. PSO is often preferred for its quicker convergence, higher tracking accuracy, and lower computational complexity, resulting in more efficient and stable performance in wind energy conversion systems. PSO usually converges faster than GA, translating to a shorter transient time (0.05 s) when the system seeks the optimal power point in varying wind conditions. It results in a more responsive system, with faster adjustments to changes in wind speed.

Nowadays, the variable speed of wind power conversion systems has already become quite important in modern wind energy generation1,2. Wind sources have become a fascinating research issue because they generate energy from the wind’s blow and have no chance of running out. It has several advantages, including being 100% natural, renewable, and sustainable. On the other hand, wind power is one of the renewable energy sources that does not require any fuel, emits no greenhouse emissions, and does not generate hazardous waste (toxic or radioactive). By fighting against climate change, wind energy contributes to the long-term maintenance of biodiversity in natural environments. For this reason, several researchers and experts are very concerned about this energy source’s ability to produce electrical energy3,4. In addition, the very principle of a wind source means that the floor area required to produce energy is relatively small, unlike solar energy. Photovoltaic panels occupy a large area for a limited maximum power because wind energy is typically stronger during the colder months. Wind energy also has the unique quality of having a larger yield in the winter. This is a significant advantage for energy grid management, as consumer demand is significantly higher during the winter period5. In recent years, governments worldwide have been investing extensively to improve operations related to renewable energy sources, due to the rising price of oil as a non-renewable resource6,7. Since wind energy is a renewable energy source, researchers are working to maximize its efficiency8,9,10,11.

Generally, WECS connected to electrical grids require several control techniques to reach the maximum power point12,13,14,15,16. PMSGs are frequently used in WECSs due to their multiple benefits, such as small size, self-excitation, high reliability, lower maintenance, the absence of a gearbox system, and reduced noise17. Consequently, the operating point of a WECS should be adjusted to maximize the efficiency of the PMSG. This technique is called MPPT17,18,19,20,21. One of many methods used in the MPPT approach improvement in this research area is the P&O technique. This approach calculates the system control based on the output power distinction between both systems (current and prior system states)15,22,23. System compensation is based on available information, such as perturbation. Therefore, determining the perturbation form in the studied system is a crucial step to achieve good results. It’s known that a small perturbation step can reduce the power losses it causes. In general, the methods applied for MPPT are fixed-step size methods. Therefore, researchers have proposed many variable-step MPPT techniques to alleviate this problem12,13,14,15,16.

The WECS operates at a variable speed, responding to fluctuating wind speeds. In this case, the wind turbines cannot operate near the optimum speed for maximum power point12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. In the same context, to locate a more powerful energy source for the system, it is necessary to have power control blocks between the PMSG and the power grid, thanks to the variable speed operation. The power regulation blocks are based on a pulse width modulation converter. Therefore, a permanent magnet (PM) generator with a high power density and efficiency can be provided. PM is highly appealing to variable speed WECS due to its benefits. Generally, the grid-side converter/inverter and generator are managed by control structures that depend on the cascaded control approach17. Additionally, due to their robustness and commonly stabilized margins, traditional proportional-integral controllers are a crucial component of the control scheme. However, the high degree of sensitivity of nonlinear systems and/or variable parameters makes PI controllers challenging. Various optimization techniques have been employed to optimize the best and/or optimal PI controllers based on parameter calculations, especially in power plants. The methods employed in this investigation partially address the issue of nonlinearity in the system under investigation.

The FLC is the primary component of this study. FLCs take a different approach to managing the nonlinear dynamic system characteristics compared to PI control strategies. The FLC is considered a design methodology; it can be employed to promote nonlinearity in the system for an integrated control approach. The FLCs possess certain essential characteristics, particularly in terms of the nonlinear system’s dynamic properties. Additionally, it relies on a model-free methodology and/or basic design specifications. Therefore, the FLC depends on the designer’s proficiency in adjusting the membership function.

It’s known that FLCs have been used in numerous studies to address various problems in electrical systems24,25,26. According to the literature, most classical FLCs depend on a fixed membership function and rule base25,26. There are cases where nonlinear systems cannot be solved with conventional FLC in great uncertainty. For this purpose, adaptive filtered approaches based on algorithms called continuous mixed-normal have been applied to update the FLC scale factors online and to enhance the productivity of a wind generator connected to the grid at variable speeds. The gray wolf optimizer algorithm is a novel nature-inspired metaheuristic designed to tackle challenging reliability optimization problems28. The outcomes produced by GWO are compared with those of several current and well-known metaheuristics, including the ant colony optimization, particle swarm optimization, and cuckoo search algorithm. Comparative analysis demonstrates that the outcomes produced by GWO are either better or on par with those produced by well-known metaheuristics. Abdulbari et al. suggest an Improved Coot optimization Algorithm based on MPPT29 to address the problem of convergence speed. With an efficiency of 99.94% and an average tracking time of 0.58 s in various weather situations, the suggested ICOA has demonstrated the best performance. A new metaheuristic MPPT method is indicated by Refaat et al. for tracking the GMPP in partial shading scenarios based on an improved autonomous group particle swarm optimization Algorithm29. The outcomes of the enhanced autonomous group PSO algorithm have been compared to those of the autonomous group PSO approaches. According to the experimental data, the suggested EAGPSO technique exhibits the lowest power oscillations, at approximately 2.03% of the monitored power, with a tracking period of 2.6 s, and achieves the highest MPPT effectiveness of 98.6% among the studied MPPT strategies. Hermassi et al. suggest a new approach based on ANFIS MPPT control in various wind-sopped turbines. When compared to alternatives, the method shows efficacy, accuracy, and a quicker reaction time in wind speed estimation and precise MPPT30. A hardware implementation of a Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) system that incorporates a pitch angle control system and sensorless wind speed prediction using the Takagi-Sugeno (TS) Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS). using the Field Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) Zed-Board is presented by Hermassi et al31.. The suggested MPPT-based TS-ANFIS approach exhibits a lower static inaccuracy of 0.02% and a rapid response time of 0.001 s. For variable-speed wind turbines (VSWT), Shutari et al. introduced a novel MPPT algorithm development based on parabolic prediction techniques (PPT) to maximize wind power extraction and improve efficiency. The simulation results confirm that the proposed PPT-MPPT algorithm outperforms the other algorithms in terms of extracted power and tracking efficiency, indicating an effective method for enhancing the VSWT system32. To optimally design control schemes (ODCSs) of frequency converters within grid-connected WPGS, SHUTARI et al. examine the application of five optimization algorithms: the hybrid sine cosine algorithm-transient search optimizer (HSCATSO), particle swarm optimizer (PSO), grey wolf optimizer (GWO), transient search optimization (TSO), and sine cosine algorithm (SCA). According to the comparison analysis’s findings, the ODCS created with HSCATSO outperformed the ODCS using SCA in terms of system stability and conversion efficiency, achieving a conversion efficiency of 98.57%. On the other hand, the ODCSs created with PSO showed the least system stability and the lowest conversion efficiency, at 93.79%. This result confirms that ODCSs play a significant role in enhancing WPGS performance and efficacy in the face of the aforementioned difficulties33.

In designing an MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking) controller using fuzzy logic for renewable energy applications, defining the membership functions (MFs) is a critical step. Membership functions determine how input variables, such as wind speed or power error, are mapped to fuzzy sets, thereby influencing the controller’s accuracy and response.

This paper presents a wind power system connected to grids controlled by different techniques to achieve good MPPT. Particle swarm optimization or genetic algorithms can automatically adjust MF limits by minimizing an objective function (e.g., error in tracking the maximum power point). The algorithm searches for the optimal bounds that yield the best Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) performance. Metaheuristic algorithms stand out for their ability to efficiently navigate large solution spaces, often outperforming traditional optimization methods in terms of effectiveness and computational efficiency. We also examined the various structures characteristic of electrical energy systems.

This paper proposes that FLCs employ various methodologies to enhance the performance of grid-tied WEC-PMSG systems. The primary objective of this study is to conduct a comparative analysis of various proposals for controlling the entire system. The novelty of Fuzzy Logic Control optimized with PSO and GA techniques for grid-tied wind energy conversion lies in its ability to effectively address the challenges inherent in wind energy systems, such as fluctuating wind speeds and grid voltage variations, by combining the adaptability of fuzzy logic with the optimization power of PSO and GA while maximizing energy yield, ensuring grid stability, and enhancing overall system performance. This approach represents a significant advancement in integrating renewable energy and grid management. To reach an informed decision regarding the system’s power, we apply the P&O technique in the second section. Non-optimized FLC is applied in the third section. FLC optimized by GA is involved in section four, and FLC optimized by PSO is used in the fifth section.

The paper is structured as follows: an overview of the study, outlining the importance of designing an FLC-based MPPT controller in grid-tied wind turbines, is given in Sect. “Introduction”. The methodology section outlines the four different methods employed in the study: the perturb and observe technique, Fuzzy logic control without optimization, optimization of FLC using PSO, and optimization of FLC using GA. These methods are described in Sect. “Methodology”. The study’s findings include an analysis of output voltage, current waveforms, power waveforms, intermediate circuit voltage waveform, and generator speed, which are presented in Sect. “Simulation outcomes and discussion”. Finally, the study’s findings are presented in Sect. “Conclusion”. It includes an analysis of output voltage, current waveforms, power waveforms, intermediate circuit voltage waveform, and generator speed.

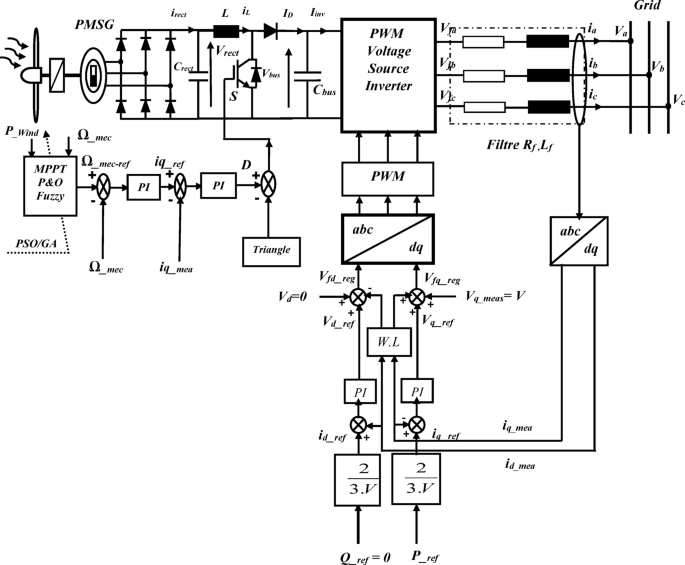

This research focuses on a system that connects wind energy to the power grid as a sustainable energy source. The WECS is used and implemented as the primary energy source, consisting of a PMSG type with a capacity of 5.5 kW. Figure 1 depicts a general diagram of a wind energy conversion system, which consists primarily of a PMSG Machine, the WECS, a diode rectifier, a static DC-DC converter (boost) to adjust the load with the WECS tied to the grid, and a DC-AC inverter linked to the grid. The architecture of a direct-drive PMSG-based WECS, in which the wind generator is associated with the PMSG. The PMSG generates electrical power, fed into the network or delivered to a destination through a voltage control converter. Typically, the two sides of the machine converter and the grid converter are directly connected to the DC-link. To optimize the presented wind turbine system using the developed FLC optimization applied to the WECS-PMSG system tied to the grid. Generally, it comprises a WECS, a PMSG, two power converters connected back-to-back by a DC link capacitor, a step-up transformer, and a dual-circuit transmission line.

The PMSG characteristics indicators are given in Tables 1 and 2.

The wind power system architecture.

The system under consideration uses a wind turbine containing blades of length L to operate a generator through a gain multiplier K. According to Bates’ law, the mechanical power that was captured by the wind turbine blades is (beta)defined as12:

Where, ρ represents the air density (kg/m3), R denotes the turbine radius (m), Vw denotes the wind velocity (m/s), and Cp is the turbine power coefficient represented as the ratio of the turbine power to the power of the wind stream. The tip speed ratio is defined by and Ωt is the rotational speed of the wind generator.

The performance indicator Cp is defined as12.

Where ({lambda _i}) is a speed point ratio, is the blade step angle.

Figure 2 depicts the characteristics of the performance coefficient and Pw=f(Ω) for a variation of wind speeds, demonstrating how the optimal power point on every curve corresponds to a particular rotation speed.

(a) Power and (b) properties of the performance coefficient at various wind speeds.

The wind turbine’s aerodynamic torque can be calculated as12.

The Gearbox model:

The following equations express the permanent magnet machine model in Park’s coordinate system13

The electromagnetic force (Tem) by Permanent magnet synchronous generator is given as14:

The DC-DC boost converter equation represented as15:

In the other way, the DC-AC link is modelled by the relation as follows15:

The voltages at the output of the inverter are written as15:

With f1, f2, and f3 presents the switching function.

The three-phase mathematical structure of inverter linked to grid model can be writing in the following equation after Park’s transformation:

With Vd,Vq, Vfd, Vfq are the grid voltages in the (d, q) axes and the output voltages of the inverter, respectively.

In renewable energy systems, bus voltage control significantly affects MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking) control, as it determines how effectively energy from the source (such as wind turbines or PV arrays) is transferred to the load or grid. The closed-loop current of the DC-DC conversion is obtained from Eq. (8) using the Laplace transformation to find the transfer function. The transfer function is used to find the PI controller in the following form16:

With (T=frac{r}{{{V_{bus}}{K_i}}})

Where, Ki is the integral control and Kp is the proportional control. The expression of the proportional-integral control is given as ({K_i}=frac{r}{{T.{V_{bus}}}}) and ({K_p}={K_i}frac{L}{r}).

As seen in Fig. 1, the inductor current is controlled by the turbine speed error. The speed error is the variance between the commanded and actual speeds (as determined by the maximum extraction algorithm of power). This error is introduced in a PI-type regulator, which is used to command a DC-DC device.

A conventional PI regulator must be added before the converter to set the DC bus voltage at the optimal value required by the grid. In the Laplace domain, the closed-loop transfer function utilizing the PI regulator and the characteristic polynomial appears like this16:

To find the expressions of the PI regulator, we impose two complex conjugate poles on the characteristic closed-loop polynomial: ({S_{1,2}}=rho left( {1 pm j} right))

Where:

The identification of the two Eqs. (14) and (15) term by term allows us to write:

({K_p}=2rho {C_{bus}}) and ({K_i}=2{rho ^2}{C_{bus}})

Figure 3 shows a DC bus voltage control loop designed to maintain a stable voltage. The reference voltage Vbus−ref is compared to the actual bus voltage Vbus to generate an error signal. This error is processed by a PI controller, which outputs a control signal to regulate the voltage. A feedback loop ensures continuous adjustment for voltage stability.

DC bus voltage control Loop.

We can independently control the active and reactive power flow between the inverter and the grid by using a vector. The injection of grid current control regulates the output currents of the inverter, which are nearly in phase with the grid voltage and exhibit minimal distortion. The Park components can be used to express the active (P) and reactive (Q) power flowing through the inverter13.

When the filter’s losses are neglected:

Vfq = Vq= |V| and Vfd = Vd = 0

If the reactive power Qref is regulated by setting idref = 0, the Eq. (16) yields the relationship. Pref is the optimum power which is provided by the MPPT approach Pref = Pw= (3/2)Viq.

The grid-side currents can be controlled using current vector control through the Park’s reference frame. The electrical filter was constructed as follows, based on the reference13.

Using a standard decoupling step and Eq. (16), we get:

With ({e_d}={L_f}omega {i_q}),({e_q}= – {L_f}omega {i_d})

The closed loop is currently controlled by:

We used two current PI controllers (direct and quadrature) to control the filter elements. Following this operation, the reference voltages (Vdref, Vqref) used in the control system can be determined.

The WECS is primarily composed of a wind turbine, characterized by its ability to harness energy from the mass of moving air. The bell-shaped power curve of wind turbines necessitates a search for the optimal operating position. We’re talking about power maximization, or tracking the maximum power point. It’s indeed necessary to describe the controller parameters that will be used to ensure operation under these ideal circumstances. This necessitates an investigation into optimizing the MPPT algorithm for wind power conversion.

The perturbation and observation technique is the most popular in the industrial setting since it is very easy to use. This solution disrupts the system by altering the module’s running speed and assessing the impact on the output power characteristics17,18,19,20.

The fuzzy logic control takes its place in the regulation chain in the same way as a traditional regulator, utilizing linguistic rules and other elements. The MPPT mechanism, developed based on the concept of fuzzy sets, is used. It is relatively simple to describe the behavioral rules that must be followed for the system to converge to the optimal position. These criteria are founded on differences in wind power ΔPw and wind turbine rotation speed ΔΩ. Table 3 and equations (21) are adapted using as inputs and outputs of the FLC, respectively (i.e., ΔPw, ΔΩ and ΔΩ_ref).

Design of the classic fuzzy MPPT controller applied by WECS.

Figure 4 illustrates the design of the fuzzy maximum power point tracking (MPPT) controller used in WECS. The fuzzy MPPT mechanism is determined through the measure of the wind power fluctuation ΔPw, and the rotational speed ΔΩ. The wind turbine provides a variation ΔΩ_ref of the rotational speed set point Ω_ref. The wind turbine speed is controlled to maintain the reference speed obtained at the output of the fuzzy controller. The wind turbine’s speed control matches the reference speed output by the fuzzy controller. Specifically, the electromagnetic torque relationship of the machine is determined by the output of the speed controller. Fuzzification, inference, and defuzzification are the three key components of a fuzzy controller in this scenario15.

Membership functions of: ΔPw, ΔΩ and ΔΩ_, ref.

Figure 5 shows Membership functions of: ΔPw, ΔΩ and ΔΩ_, ref. in the First, a set of fuzzy input variables and a membership function are defined. The fuzzy input in our investigation are the variation in power (Pw) and the variation in speed ΔΩ. Due to their simplicity, we adopted a combined trapezoidal and triangular membership functions for the input variables (ΔPw and Δ) and the output variable Δ_, as referenced.

Tuning membership functions is crucial in designing a compelling fuzzy logic maximum power point tracking (MPPT) controller. Tuning ensures that the MFs align with the system’s operational requirements and respond optimally to changes in inputs. This tuning process occurs both before and after optimization, using algorithms such as particle swarm optimization or genetic algorithms. Each stage has distinct goals and impacts on the MPPT controller’s performance. Summary of key differences between perior and following PSO/GA is illustrated in Table 4.

The used fuzzy rules are: Negative Big (NB), Negative Small (NS), Zero (Z), Positive Small (PS), and Positive Big (PB). The regulator’s final step is defuzzification, which turns the fuzzy rules’ values of ΔΩ−ref into a digital value. The defuzzification approach is the gravity center, and Mamdani’s reasoning is used for fuzzy inference16.

Optimization techniques can address a wide range of problems, such as locating function zeros, minimizing the distance between measurement points and curves, finding function intersections, and solving systems of equations involving one or more parameters.

In 1995, Kennedy and Eberhart presented the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) approach, a meta-heuristic optimization tool20. The PSO method utilizes several particles dispersed throughout the search region. Since every particle has a random speed, the technique depends on the particle’s position and speed. The PSO approach utilizes a swarm made up of np∈N particles({({X_i})_{i=1,2,…..{n_p}}}). In search of the suboptimal ({X^ * } in {N^{q+1}}) a method to reduce the goal function, also referred to as(:Jin:mathbb{R}). The velocity at which the particle vectors move (:{i}^{th})are provided respectively by Xi = (Xi,1, Xi,2…….,Xi, q) and Vi = (Vi,1, Vi,2…….Vi, q). The following iterative expressions determine them17,21,22,23,24,25:

To determine the correct response, the GA simulates the natural development process. Key GA ideas include encoding, population initialization, fitness function, genetic operators, and elite reservation method26,27, which can be described as follows:

Step 1: Initiate a population in the search space with N chromosomes generated randomly. the(chromosome=[{X_1},{X_2}…..,{X_n}]), where ({X_{hbox{min} }} leqslant {X_{1,2,…..,n}} leqslant {X_{hbox{max} }}).

Step 2: Calculate each chromosome’s goal function.

Step 3: Execute the following instructions.

(a) Reproduce, that is, choose the best chromosomes with a probability depending on their values for the objective function.

(b) Utilizing the crossing probability, cross the chromosomes you chose in the previous step.

(c) Apply a mutation probability modification to the chromosomes generated in the preceding step.

Step 4: The operation can be terminated if the stopped condition occurs or even if the ideal solution is found. Alternatively, repeat steps 2 through 4 until the stop condition is met.

Step 5: The suitable solution({X^ * }), matching the ideal objective function, ({X^ * }={hbox{min} _{X_{i}^{j}}}left( {J(X_{i}^{j}),forall i,j} right))

The solution to an optimization problem yields the fuzziness’s twenty-one parameters, which represent the limit of the membership function inside the fuzzy system. Minimum and maximum values of input variables (∆P and ∆Ω) are from − 1 to + 1. Minimum and maximum values of output variables (∆Ωref) are from − 1 to + 1. The objective function displays the total of the Mean Squared Errors (MSE). The error in this case is the variation between the computed value from the simulated system and the maximum power provided by the wind turbine at a wind speed of 12.3 m/s at each sampling time k. Hence, get the following formula:

Schema illustrating the fuzzy MPPT controller’s PSO/GA tuning procedure.

Figure 6 presents a schematic of a fuzzy MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking) controller incorporating a PSO and GA based tuning procedure. The system is designed to extract the maximum power from a wind energy conversion system by adjusting the reference rotor speed. The inputs to the fuzzy controller are the change in power Δ[] and the change in rotor speed ΔΩ[k], calculated using the current and previous values of wind power [] and rotor speed Ω[]. These inputs pass through fuzzification blocks, where they are converted into fuzzy linguistic variables and then processed by a rule base to generate the output: the change in reference speed ΔΩref[]. This output is then defuzzified and added to the previous reference speed Ω[−1] to generate the updated reference speed Ω ref [k]. The new reference speed is compared with the measured rotor speed Ω meas [k], and the resulting error is fed to a PI controller, which generates the electromagnetic torque command to drive the generator accordingly.

Fuzzy membership functions optimized using two different metaheuristic algorithms: (a) Genetic Algorithm (GA) and (b) Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO).

Figure 7 presents the fuzzy membership functions optimized using two different metaheuristic algorithms: (a) Genetic Algorithm (GA) and (b) Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). Each column of subplots shows the membership functions for the fuzzy controller inputs and output after optimization. For both GA and PSO tuning, the fuzzy variables include: ΔPw : change in power,ΔΩ: change in rotor speed,ΔΩ: change in reference speed. Each fuzzy variable is associated with seven linguistic terms: NB (Negative Big), NM (Negative Medium), NS (Negative Small), Z (Zero), PS (Positive Small), PM (Positive Medium), and PB (Positive Big). These terms are represented as triangular membership functions that define how input or output values are fuzzified in the controller. In subplot (a), the membership functions are tuned using the Genetic Algorithm, resulting in some asymmetry and varied spacing among the functions, which reflects the algorithm’s attempt to adapt more precisely to system dynamics based on performance evaluation (fitness). In subplot (b), the Particle Swarm Optimization method was used. The functions are generally more symmetric and smoother compared to those of GA, exhibiting a different distribution strategy for optimizing fuzzy controller performance. Overall, the figure illustrates how GA and PSO can be utilized to fine-tune fuzzy controllers, yielding optimized membership functions that enhance MPPT performance in dynamic systems, such as wind energy conversion systems.

The PSO/GA block evaluates a fitness function and optimizes the fuzzy logic controller’s parameters (such as membership functions or rule weights) to improve MPPT efficiency. The combination of fuzzy logic and evolutionary algorithms allows the controller to adaptively and intelligently track the maximum power point under varying wind conditions.

Objective function: (a) Genetic Algorithm, (b) Particle Swarm Optimization.

The value of the objective function, or fitness function, when attempting to find the best response is displayed in Fig. 8. The iteration number is 70 when no decrease in total control error was observed. It’s important to indicate the variation between both Fig. 8.a and Fig. 8.b at the level of the convergence.

Table 5 depicts the function of membership tuning Prior to and following the PSO/GA parameters.

A MATLAB/Simulink tool is used to simulate the entire system, validating the proposed system design with the suggested control. The source of wind energy is modeled to predict its actual characteristics. In this analysis, a step-change wind speed profiles are used.

A step-change wind speed profiles.

Figure 9 illustrates a step-change wind speed profile over a time interval from 0 to 1 s. he wind speed starts at approximately 12.5 m/s, remains constant until about 0.3 s, then drops abruptly to 8 m/s, where it stays until about 0.6 s. After 0.6 s, the wind speed steps up again to 10 m/s and remains constant until the end of the time interval at 1 s. This profile is used in these simulations to test the system’s response under sudden wind speed variations.

Turbine’s optimal speed.

Figure 10 illustrates the optimum mechanical speed variation of the turbine. It can be seen that the optimum speed of the turbine is achieved at a wind speed of v = 12.3 m/s (70 rps). This figure also illustrates that the mechanical speed converges well towards their optimal value after an acceptable response time (tresp), i.e.:

tresp=0.07s for the P&O algorithm; tresp =0.055 s for Fuzzy; tresp =0.015 s for the Fuzzy-GA; tresp =0.05 s for the Fuzzy-PSO algorithm. After adjusting the wind speed to 8 m/s, the values illustrate that the wind source speed has tuned to its new optimum value of 45 rps. After a further increase in the wind level to 10 m/s, the speed was readjusted to a new optimal point, i.e. 57rps. It can be observed that the Fuzzy-PSO reaches MPP faster than other controllers. The steady-state behavior of the WECS using the Fuzzy-PSO method is more stable compared to other MPPT methods. It is essential to present the torque dynamics, the DC-DC conversion current, and the mechanical power in a consistent manner with the wind speed.

Optimal torque.

Figure 11 compares the optimal torque responses of four control strategies —P&O, Fuzzy, Fuzzy-GA, and Fuzzy-PSO — under varying wind speeds. The Fuzzy-PSO controller consistently achieves the highest and most stable torque values with minimal overshoot and fast settling time, making it the most effective. In contrast, the P&O method exhibits significant overshoot and a slower response, especially during rapid changes in wind speed. The Fuzzy and Fuzzy-GA controllers perform moderately well, with smoother responses but slightly lower torque tracking accuracy compared to Fuzzy-PSO. Overall, Fuzzy-PSO demonstrates superior performance in dynamic wind conditions.

Current of DC-DC converter.

Figure 12 illustrates the current response (Iq) of a DC-DC converter under four control strategies: P&O, Fuzzy, Fuzzy-GA, and Fuzzy-PSO. The P&O method exhibits significant overshoot and oscillations, indicating poor dynamic performance. The basic Fuzzy controller exhibits smoother transitions, albeit with a slower response and lower steady-state current. Fuzzy-GA improves stability and response time over the basic Fuzzy method. Among all, the Fuzzy-PSO controller demonstrates the best performance with rapid response, minimal overshoot, and stable tracking of current changes, making it the most effective strategy in this comparison.

Optimal mechanical power.

Figure 13 compares the optimal mechanical power tracking of four control strategies, highlighting that Fuzzy-GA and Fuzzy-PSO outperform the traditional P&O and basic Fuzzy controllers. While P&O exhibits slow rise times and delayed responses to power changes, both Fuzzy-GA and Fuzzy-PSO achieve fast and accurate tracking with minimal overshoot or oscillation. The Fuzzy controller performs better than P&O but remains less effective than its optimized versions. Overall, Fuzzy-PSO shows the best performance, ensuring rapid convergence and stable power regulation across all operating conditions.

Active and reactive power.

Figure 14 displays the outcomes of the grid-side simulation, including the changes in active and reactive power over the simulation duration. The electrical quantities converge toward their optimum powers for every wind speed variation. Since the inverter injects the active power into the grid, the reactive power is set to zero (Q_ref = 0). This demonstrates how effectively the applied regulation loop operates.

Reference current injected into the grid.

According to the results presented above (Fig. 15), the reference current injected into the grid converges precisely towards the optimal current and after an acceptable response time. This time is shorter relative to the dynamic system. In addition, the current injected to the inverter Iq is equal to −18 A. But, after an acceptable response time of 0.006s, it increases to the value of about − 5 A. The current decreases to the value of −10 A due to the variation of the source (wind); as we see that the current Id injected into the inverter is zero regardless of the power variation.

Measured current injected into the grid.

The measurement current injected into the network, as depicted in Fig. 16, converges satisfactorily towards the desired current within an acceptable response time. This time is relatively shorter compared to the dynamic system, which is slow (source of the wind). We note a good response time and effective monitoring of the controlled system.

Three-phase voltage of the grid.

The three-phase voltage grid and the current injected into the grid are shown in Fig. 17. The current is depicted in this picture as having a 50 Hz sinusoidal three-phase form.

Figure 18 presents the three-phase current waveform of a grid system, demonstrating dynamic changes in amplitude corresponding to different operating conditions. Initially, the currents are high and sinusoidal, then drop significantly between 0.25 s and 0.6 s, likely due to a change in load or a system event. After 0.6 s, the currents increase again and remain balanced. The inset confirms the sinusoidal and symmetrical nature of the currents, indicating a healthy and synchronized three-phase grid operation throughout the time frame, despite transient variations.

Three-phase current of the grid.

Zoom of single phases voltage (Va) and current (Ia) of grid.

Dc link voltages.

The grid’s phase voltage and current are displayed in Fig. 19. With a fundamental frequency of 50 Hz, it is evident that the grid-side inverter current waveforms are in phase with the grid phase voltage waveforms.

Figure 20 shows the DC link voltage, which is maintained at the reference voltage regardless of wind variations (VDC = 800 V). This conservation aims to ensure the conversion and transfer of energy to the grid.

Table 6 illustrates a comparative summary table showing performance indicators for all MPPT methods.

In this study, we focused on enhancing the performance of grid-tied wind energy conversion systems (WECS) by optimizing fuzzy logic control (FLC) using Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithm (GA) techniques. By integrating these advanced optimization methods, we aimed to enhance the efficiency and stability of wind energy conversion systems (WECS) operations. Extensive simulations and analyses confirmed the effectiveness of the proposed approach, demonstrating significant performance improvements under various operating conditions. The results underscore the value of FLC optimization, particularly through PSO and GA, in achieving robust and efficient wind energy conversion.

To evaluate the control strategies, four approaches were tested: P&O, Fuzzy, Fuzzy-GA, and Fuzzy-PSO under varying wind speeds. Among these, the Fuzzy-PSO controller consistently achieved the highest and most stable performance, with minimal overshoot and fast settling time, establishing it as the most effective strategy. In contrast, the P&O method exhibited significant overshoot and a slower response, especially during rapid changes in wind speed. The Fuzzy and Fuzzy-GA controllers demonstrated moderate performance, providing smoother responses but slightly lower tracking accuracy compared to the Fuzzy-PSO controller. Overall, Fuzzy-PSO demonstrated superior performance in dynamic wind conditions. Our research also highlights the practical benefits of these strategies, including the system’s adaptability to changing environmental conditions while maintaining optimal power output. The simplicity and feasibility of the proposed control strategies support their integration into real-world grid-connected applications.

Looking ahead, future work could involve experimental validation of the proposed control schemes on a physical test bed to assess real-world performance and identify implementation challenges. Investigating system robustness under varying grid conditions, such as voltage fluctuations and frequency deviations, would also strengthen the reliability of the approach. Additionally, incorporating wind speed profiles with continuous, non-step variations would provide a more realistic simulation environment, better reflecting the stochastic nature of wind in real-world scenarios. Overall, this research contributes to the advancement of renewable energy technologies by providing valuable insights into the application of intelligent optimization techniques for enhancing the efficiency, reliability, and adaptability of grid-tied wind energy conversion systems (WECS).

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article omitted an affiliation for Ayman Hoballah. The article has been corrected.

Wind energy conversion system

Fuzzy logic controller

Perturb and observe

Genetic Algorithm

Particle swarm optimization

Permanent magnet synchronous generator

Pulse width modulation

Permanent magnet

Continuous mixed-normal

Grey Wolf Optimizer

Improved Coot Optimization Algorithm

Wind energy conversion

Doubly-fed induction generator

Enhanced autonomous group Particle Swarm Optimization

Continuous mixed-normal

Reference active power

Reference reactive power

Resistor of the filter

Inductor of the filter

Input Inverter current

Inductor current of the boost converter

Power of wind

Duty cycler

Bus voltage

Bus capacitor

Rectifier capacitor

Reference direct current and measured direct current

Reference quadrature current and measured quadrature current

Bukar, A. L., Tan, C. W., Yiew, L. K., Ayop, R. & Tan, W. S. A rule-based energy management scheme for long-term optimal capacity planning of grid-independent microgrid optimized by multi-objective grasshopper optimization algorithm. Energy. Conv. Manag. 221, 113161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113161 (Oct. 2020).

Soliman, M. A., Hasanien, H. M., Azazi, H. Z., El-Kholy, E. E. & Mahmoud, S. A. Linear-Quadratic Regulator Algorithm-Based Cascaded Control Scheme for Performance Enhancement of a Variable-Speed Wind Energy Conversion System, Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 2281–2293, Mar. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-018-3433-6

Pan, L. & Shao, C. Wind energy conversion systems analysis of PMSG on offshore wind turbine using improved SMC and Extended State Observer, Renewable Energy, vol. 161, pp. 149–161, Dec. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.06.057

Wang, J. et al. Maximum power point tracking control for a doubly fed induction generator wind energy conversion system based on multivariable adaptive super-twisting approach. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 124, 106347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2020.106347 (Jan. 2021).

Bouketta, S. & Bouchahm, Y. Numerical evaluation of urban geometry’s control of wind movements in outdoor spaces during winter period. Case of mediterranean climate. Renew. Energy. 146, 1062–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.07.012 (Feb. 2020).

Xydis, G. & Mihet-Popa, L. Wind energy integration via residential appliances. Energ. Effi. 10 (2), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-016-9459-2 (Apr. 2017).

Diesendorf, M. & Wiedmann, T. Implications of trends in energy return on energy invested (EROI) for transitioning to renewable electricity. Ecol. Econ. 176, 106726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106726 (Oct. 2020).

Deltenre, Q., de Troyer, T. & Runacres, M. C. Performance assessment of hybrid PV-wind systems on high-rise rooftops in the Brussels-Capital region. Energy Build. 224, 110137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110137 (Oct. 2020).

Dong, F. & Shi, L. Regional differences study of renewable energy performance: A case of wind power in China. J. Clean. Prod. 233, 490–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.098 (Oct. 2019).

Idriss, A. I., Ahmed, R. A., Omar, A. I., Said, R. K. & Akinci, T. C. Wind energy potential and micro-turbine performance analysis in Djibouti-city, Djibouti, Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 65–70, Feb. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2019.06.004

Wang, Z., Wang, S., Ren, J., Meng, X. & Wu, Y. Model experiment study for ventilation performance improvement of the wind energy fan system by optimizing wind turbines. Sustainable Cities Soc. 60, 102212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2020.102212 (Sep. 2020).

Ayrir, W. & Haddi, A. Fuzzy 12 sectors improved direct torque control of a DFIG with stator power factor control strategy. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 29 (10), e12092. https://doi.org/10.1002/2050-7038.12092 (Oct. 2019).

Borni, A. et al. Fuzzy logic, PSO based fuzzy logic algorithm and current controls comparative for grid-connected hybrid system, AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 1814, no. 1, p. 020006, Feb. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4976225

Doubly Fed Induction Machine. Modeling and Control for Wind Energy Generation Applications | IEEE eBooks | IEEE Xplore. accessed Jan. 09, (2022). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/book/6047757

Abdelhalim, B. et al. Optimization of the fuzzy MPPT controller by GA for the single-phase grid-connected photovoltaic system controlled by sliding mode, AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 2190, no. 1, p. 020003, Dec. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5138489

María, A., Mantilla, Johann, F. & Petit Gabriel Ordóñez,Control of multi-functional grid-connected PV systems with load compensation under distorted and unbalanced grid voltages, Electric Power Systems Research,Volume 192,2021,106918,ISSN 0378–7796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2020.106918

Harrag, A. & Messalti, S. PSO-based SMC variable step size P&O MPPT controller for PV systems under fast changing atmospheric conditions. Int. J. Numer. Modelling: Electron. Networks. 32 (5). https://doi.org/10.1002/jnm.2603 (2019). Devices and Fields.

Sedraoui, M. et al. Development of a fixed-order H_{infty } controller for a robust P&O-MPPT strategy to control poly-crystalline solar PV energy systems. Sci. Rep. 15, 2923. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86477-y (2025).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Borni, A. et al. Design, Analysis and Implementation of Fixed and Variable Step Incremental MPPT Techniques of PV Power Conversion System, 2024 IEEE International Multi-Conference on Smart Systems (IMC-SSGP), Djerba, Tunisia, pp. 1–5, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/IMC-SSGP63352.2024.10919801

Borni, A. et al. Design and Implementation of Efficient Low Cost MPPT Controller for Photovoltaic Application, 2023 14th International Renewable Energy Congress (IREC), Sousse, Tunisia, pp. 1–6, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/IREC59750.2023.10389279

Farh, H. M. H., Eltamaly, A. M., Ibrahim, A. B., Othman, M. F. & Al-Saud, M. S. Dynamic global power extraction from partially shaded photovoltaic using deep recurrent neural network and improved PSO techniques. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 29 (9). https://doi.org/10.1002/2050-7038.12061 (2019).

Liu, F., Ju, X., Wang, N., Wang, L. & Lee, W. J. Wind farm macro-siting optimization with insightful bi-criteria identification and relocation mechanism in genetic algorithm. Energy. Conv. Manag. 217 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.112964 (2020).

Liu, B. et al. K-PSO: an improved PSO-based container scheduling algorithm for big data applications. Int. J. Netw. Manage. 31 (2). https://doi.org/10.1002/nem.2092 (2021).

Bhatti, A. R. et al. Optimized sizing of photovoltaic grid-connected electric vehicle charging system using particle swarm optimization. Int. J. Energy Res. 43 (1). https://doi.org/10.1002/er.4287 (2019).

Devasahayam, V. & Veluchamy, M. An enhanced ACO and PSO based fault identification and rectification approaches for FACTS devices. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 27 (8). https://doi.org/10.1002/etep.2344 (2017).

Deng, Q., Yu, J. & Wang, N. Cooperative task assignment of multiple heterogeneous unmanned aerial vehicles using a modified genetic algorithm with multi-type genes, Chinese Journal of Aeronautics, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 1238–1250, Oct. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CJA.2013.07.009

WANG, Z., LIU, L., WEN, Y. & T. LONG, and Multi-UAV reconnaissance task allocation for heterogeneous targets using an opposition-based genetic algorithm with double-chromosome encoding. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 31 (2), 339–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CJA.2017.09.005 (Feb. 2018).

Kumar, A., Pant, S. & Ram, M. System reliability optimization using Gray Wolf optimizer algorithm. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 33 (7), 1327–1335. https://doi.org/10.1002/qre.2107 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Mohammed, A. T. N. K. K. Nur Fadilah Ab aziz, Karmila Binti kamil, Saad mekhilef,improved Coot optimizer algorithm-based MPPT for PV systems under complex partial shading conditions and load variation,energy. Convers. Management: X Volume 22,2024,100565, ISSN 2590 – 1745, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecmx.2024.100565

Ahmed Refaat, A. E., Khalifa, M. M., Elsakka, Y., Elhenawy, A. & Kalas Medhat Hegazy elfar,a novel metaheuristic MPPT technique based on enhanced autonomous group particle swarm optimization algorithm to track the GMPP under partial shading conditions – Experimental validation,energy conversion and management,287,2023,117124,issn 0196–8904, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2023.117124

Hermassi, M. et al. Wind speed Estimation and maximum power point tracking using neuro-fuzzy systems for variable-speed wind generator. Wind Eng. 48 (6), 1088–1104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309524X241247231 (2024).

Article Google Scholar

Hermassi, M., Krim, S., Kraiem, Y. & Hajjaji, M. A. Zynq FPGA for hardware co-simulation of Takagi-Sugeno neuro-fuzzy for MPPT algorithm incorporating sensorless wind speed Estimation in grid-connected wind system. J. Eng. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jer.2024.09.017 (2024).

Article Google Scholar

Shutari, H. et al. Development of a novel efficient maximum power extraction technique for Grid-Tied VSWT system, in IEEE access, 10, pp. 101922–101935, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3208583

Shutari, H. et al. Comparative analysis of optimization algorithms to enhance WPGSs performance: Malaysia case study. IEEE Access. 12, 174818–174830. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3418524 (2024).

Article Google Scholar

Download references

The authors would like to acknowledge the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Taif University for funding this work.

This work is funded and supported by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Taif University.

Centre de Développement des Energies Renouvelables, Unité de Recherche Appliquée en Energies Renouvelables, URAER, CDER, Ghardaïa, 47133, Algeria

Abdelhalim Borni, Layachi Zaghba & Abdelhak Bouchakour

Department of Electrical Engineering, Fac. Technology, University of El Oued, El-Oued, 39000, Algeria

Noureddine Bessous

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Debre Markos Institute of Technology, Debre Markos University, P. O. Box 269, Debre Markos, Ethiopia

Melkamu Sisay Agmas

Centre for Research Impact & Outcome, Chitkara University Institute of Engineering and Technology, Chitkara University, Rajpura, 140401, Punjab, India

Enas Ali

Department of Electrical Engineering, College of Engineering, Taif University, Taif, 21944, Saudi Arabia

Sherif S. M. Ghoneim & Ayman Hoballah

Electrical Power and Machines Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Tanta University, Tanta, 31521, Egypt

Ayman Hoballah

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

Abdelhalim Borni, Noureddine Bessous, Layachi Zaghba, Abdelhak Bouchakour: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Melkamu Sisay Agmas, Enas Ali, Sherif S. M. Ghoneim, Ayman Hoballah: Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Project administration, Funding Acquisition.

Correspondence to Melkamu Sisay Agmas.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

Borni, A., Bessous, N., Zaghba, L. et al. Enhancing grid connected wind energy conversion systems through fuzzy logic control optimization with PSO and GA techniques. Sci Rep 15, 27678 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12593-4

Download citation

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12593-4

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Advertisement

Scientific Reports (Sci Rep)

ISSN 2045-2322 (online)

© 2026 Springer Nature Limited

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.