Guest Column | January 30, 2026

By Denise N. Bronner, Ph.D., CEO and founder, Empactful Ventures

For decades, the U.S. has served as the default anchor for global clinical development. From early feasibility through pivotal execution, the U.S. offered a familiar combination of scientific leadership, regulatory influence, and deep investigator networks. Yet the global trial footprint is changing, and the shift is becoming measurable.

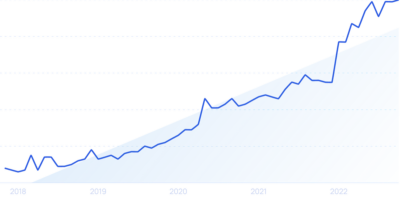

In a recent Cell & Gene State of the Industry Briefing session during JPM 2026, a speaker shared that 919 trials were conducted in the U.S. compared with 990 across APAC, marking a notable inflection point: APAC is no longer simply a complementary region for cost efficiency or enrollment support. It is increasingly competing as a primary engine of trial activity, with implications for operational strategy, patient recruitment models, regulatory evidence expectations, and the future design of trials themselves.

This change is not driven by a single factor. Rather, it reflects a convergence of political, economic, and workforce pressures in the U.S., paired with rapid execution maturity across APAC and other global regions.

The rise in APAC trial activity is increasingly visible across the broader ecosystem of supply routes, CRO footprints, and sponsor site strategies. Industry reporting has described increasing clinical trial activity across APAC as influencing global commercial planning and infrastructure decisions, reinforcing the idea that the region’s role is expanding beyond support into center of execution.1

While APAC is often discussed as one unified region, the reality is more nuanced. Trial growth is not limited to China; multiple APAC markets are gaining prominence based on therapeutic focus, speed of start-up, and site availability. Recent industry analysis has highlighted APAC’s rising stars beyond China, reflecting broader expansion in where sponsors can place programs.2

Clinical trials do not exist outside the policy environment. Shifts in government priorities and political rhetoric can influence research funding, public-private investment signals, and the stability of community research infrastructure. For programs that rely on public-facing recruitment, diverse enrollment, and multisite participation, uncertainty can translate into slower execution and increased risk.

This is particularly relevant in the context of DEI-focused clinical research investments. If grant mechanisms and related priorities experience contraction or instability, downstream effects appear quickly: fewer community-based partnerships, reduced site enablement, and less durable infrastructure for sustained recruitment across underrepresented populations.

The U.S. recruitment challenge is often framed as a patient awareness gap, but the underlying issues extend beyond marketing. Rising healthcare costs can reduce patient capacity to participate in research even when interest is present. Other regions, including APAC, are also grappling with aging populations and rising chronic disease prevalence. Yet the U.S. cost baseline is materially higher, which compounds the hidden participation costs that make enrollment and retention harder.3-4 Participation requires time, transportation, work flexibility, and caregiver support, costs that are rarely captured in trial budgets but materially affect enrollment feasibility and retention.

Operational capacity is now a key determinant of trial performance. Clinical research coordinators, nurses, and site staff are operating under sustained strain. Turnover and burnout introduce variability into start-up timelines, protocol adherence, and patient experience. All of these are factors that directly impact cycle time and data quality. Sponsors and CROs have responded by diversifying their execution footprint into regions where staffing constraints and site throughput may be less volatile.

Historically, the U.S. benefited from large healthcare systems, broad investigator networks, and high trial density and was often described as a high-enrolling environment. But the U.S. has also struggled with recruitment for years due to eligibility stringency, site burden, and uneven patient trust. These challenges remain and, in some indications such as oncology and rare diseases5-6, they have intensified.

At the same time, sponsors are reporting more reliable enrollment performance outside the U.S., particularly across APAC and LATAM where recruitment infrastructure has matured and site performance has improved through sustained investment.7 The strategic shift is about finding more patients, partnered with predictable timelines and lower costs. As global regions demonstrate stronger performance consistency, sponsors increasingly have viable alternatives to U.S.-centered enrollment strategies.![]()

A second major force is emerging alongside geographic diversification: evolving regulatory thinking about evidence generation and the number of trials required for approval. Recent reporting and commentary have highlighted discussions at the FDA about reducing the expectation of two pivotal trials in some circumstances, potentially shifting toward a “one-trial” standard when statistical rigor and totality of evidence are sufficient.8 While the details and scope of any such change matter, the broader implication is clear: If sponsors can meet regulatory standards with fewer large trials, then speed, quality, and execution certainty become even more central.

In practical terms, fewer pivotal studies would increase the value of regions that can deliver faster start-up, stable recruitment, lower protocol deviation risk, and efficient monitoring and data turnaround. If APAC or other regions continue to improve on these levers, the shift in trial placement could accelerate.

The next five to 10 years may bring an even more profound disruption than regional redistribution. Sponsors are increasingly investing in tools such as trial simulation and predictive feasibility modeling, synthetic control arms, digital twins, and in silico trials and computational modeling.

The regulatory posture toward AI-enabled development is also evolving. On January 14, 2026, Reuters reported that the FDA and EMA issued joint guiding principles for “good AI practice” in drug development, signaling increasing regulatory alignment on responsible AI use across the life cycle.9 Meanwhile, published literature has described growing interest in digital twins and in silico trials, noting that regulators recognize the potential of computational modeling to enhance assessment processes.10

The long-term question is not whether these tools will be used, but how much they will reduce reliance on traditional participation models (e.g., animal studies and large human cohorts in certain contexts). If simulation and modeling can support earlier decisions, reduce placebo exposure, or meaningfully shrink required sample sizes, regulators will face new pressures to update evidence frameworks while maintaining safety and public trust. This adjustment will not occur overnight. Regulators are building the principles and guardrails that will eventually allow more modern evidence development approaches to scale responsibly.

The U.S. remains a critical market for innovation and commercialization, but clinical development execution is becoming more distributed and, in some areas, more competitive. APAC’s growth is part of a broader rebalancing that reflects structural pressures in the U.S. and rapid maturation elsewhere. At the same time, regulatory evolution and technology-enabled trial models are poised to reshape how evidence is generated in the future.

For sponsors, CROs, and trial leaders, the strategic priority is no longer simply to expand globally. It is to build a development model that performs under real-world constraints while preparing for an evidence landscape where simulation, digital tools, and modernized regulatory approaches may increasingly influence what enough data looks like.

The organizations that adapt early will not only execute trials faster but will ultimately shape the next generation of trial design itself.

References:

About The Author: Denise N. Bronner, Ph.D., has roughly 15 years of organizational thought leadership experience within the global healthcare space and has held various roles in academia, consulting, pharma, and venture capital. During her career, she has specialized in health equity, data-driven global therapy program strategy development, pitch and storytelling refinement, and identifying business opportunities within pharma. Beyond her professional endeavors, she's passionate about enhancing diversity in STEM fields, serving on advisory boards, participating as a judge in pitch/business competitions, and mentoring young professionals. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biological sciences from Wayne State University, a Ph.D. in microbiology & immunology from the University of Michigan – Ann Arbor, and certification from the Venture Capital Executive Program from UC Berkeley Haas School of Business. She is the founder of Empactful Ventures, which currently consults healthcare-focused startups and venture funds, and she is a member of the Clinical Leader editorial board.

Denise N. Bronner, Ph.D., has roughly 15 years of organizational thought leadership experience within the global healthcare space and has held various roles in academia, consulting, pharma, and venture capital. During her career, she has specialized in health equity, data-driven global therapy program strategy development, pitch and storytelling refinement, and identifying business opportunities within pharma. Beyond her professional endeavors, she's passionate about enhancing diversity in STEM fields, serving on advisory boards, participating as a judge in pitch/business competitions, and mentoring young professionals. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biological sciences from Wayne State University, a Ph.D. in microbiology & immunology from the University of Michigan – Ann Arbor, and certification from the Venture Capital Executive Program from UC Berkeley Haas School of Business. She is the founder of Empactful Ventures, which currently consults healthcare-focused startups and venture funds, and she is a member of the Clinical Leader editorial board.