Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

Advertisement

Scientific Reports volume 15, Article number: 44372 (2025)

575

Metrics details

Cortisol/corticosterone (CORT) are typical glucocorticoids and exert an anti-stress function. p27, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, acts as a terminal factor for Sertoli cell proliferation at the prepubescent stage. Our previous study showed neonatal CORT administration increased p27-positive Sertoli cells followed by decreasing Sertoli cells in mice. The present study evaluated the effects of CORT and/or RU 486, a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, on Sertoli cells in early life stages. CORT and/or RU 486 were subcutaneously injected to ICR mice, from postnatal days (PNDs) 1 to 10, at doses of 0.36 and 0.0006 mg/kg body weight, respectively. Testes from control, CORT-, RU 486 + CORT-, and RU 486-administered mice were evaluated on PNDs 4, 10, and 16. RU 486 administration blocked CORT-induced increase of relative p27-positive Sertoli cells, with the resultant recovery of Sertoli cell numbers to control level. RU 486 administration alone unexpectedly caused decreases in Sertoli cells. The present study is the first to reveal that activation of glucocorticoid receptors following CORT administration in early life stages is involved in p27-positive Sertoli cell and total Sertoli cell number in vivo, suggesting that appropriate glucocorticoid signaling in early life stages is required for the intact proliferation and maturation of Sertoli cells.

Cortisol and corticosterone (CORT) are typical glucocorticoids that regulate many physiological processes, including metabolism, immune function, and growth and development, among others1,2. In particular, they exert an anti-stress function. For example, under stressful situations, CORT is secreted via the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and adapts a series of each organ to stress-conditions3. In previous studies, various stresses at early life stages (Early Life Stress, ELS) and subsequent excessive and chronic secretion of CORT result in adverse health effects, in both humans and animals4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Depression and autism spectrum disorder are well known disorders for ELS or excessive and chronic CORT secretion12,13. On the other hand, our studies previously revealed that ELS or neonatal CORT administration result in disorders of the male reproductive system in mice, such as decreased testicular weight, decreased number of Sertoli cells and epididymal spermatozoa14,15,16.

p27 is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and acts as a terminal factor for Sertoli cell proliferation at the prepubescent stage17. Previous studies have reported that p27 is a target in the glucocorticoid signaling pathway. Glucocorticoids are involved in regulating the cell cycle, and act to decrease c-myc, cyclin-dependent kinase 4, 6, and cyclin D3 levels and increase p21, other cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, and p27 levels. Taken together, these effects result in cell cycle arrest in several types of cells18,19. In another study, Jiang et al. reported that administration of CORT caused the induction of p27, whereas administration of both CORT and RU 486 (mifepristone), a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, regressed p27 levels compared to treatment with CORT alone in a mouse mammary hyperplastic epithelial TM10 cell line20. The activation of glucocorticoid receptors following glucocorticoid secretion or treatment can elicit p27 upregulation in several cell types, including TM10 cell and human osteosarcoma cell lines20,21.

Our study had shown that early-life CORT administration increased the number of p27-positive Sertoli cells in vivo in mice on postnatal day (PND) 1016. However, it remains unclear that glucocorticoid receptor activation by exogenous CORT may cause the observed increases of p27-positive Sertoli cells, thereby finally affecting Sertoli cell number in vivo. The purpose of the present study is to clarify the mechanism for the effects of CORT on Sertoli cells by the use of RU 486. For this purpose, GATA-4 (a Sertoli cell marker within seminiferous tubules) -positive cell and p27-positive cell numbers were evaluated for each seminiferous tubule in testes from mice treated with CORT and/or RU 486 neonatally.

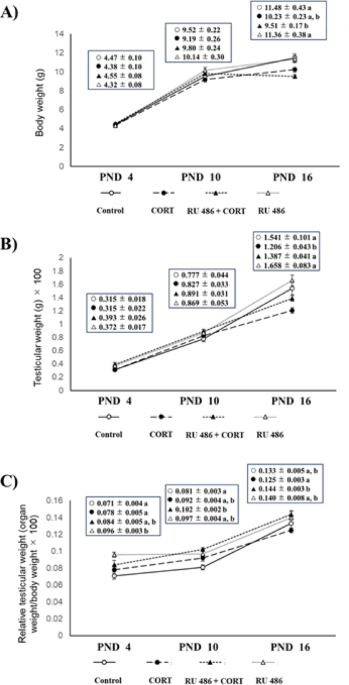

Body weight, testicular weight and relative testicular weight (formula: organ weight/body weight × 100) for each mouse groups were shown in Fig. 1A, B, and C, respectively. For body weight, extreme increase or precipitous decline were not observed among the 4 groups on PNDs 4, 10, and 16 (Fig. 1A) (Average body weights of control, CORT-, RU 486 + CORT-, and RU 486-administered mice were 4.47 ± 0.10, 4.38 ± 0.10, 4.55 ± 0.08, 4.32 ± 0.08 g on PND 4, 9.52 ± 0.22, 9.19 ± 0.26, 9.80 ± 0.24, 10.14 ± 0.30 g on PND 10, 11.48 ± 0.43, 10.23 ± 0.23, 9.51 ± 0.17, 11.36 ± 0.38 g on PND 16, respectively). For testicular weight, no significant differences were observed among the 4 groups on both PNDs 4 and 10. However, on PND 16, testicular weight was significantly lower in CORT-administered group compared with other groups (Fig. 1B). Relative testicular weight (formula: organ weight/body weight × 100) significantly increased in RU 486 + CORT-administered group compared with CORT-administered group on PND 16 (Fig. 1C).

Body, testicular weight, and relative testicular weight on PND 4, 10, and 16 in CORT- and/or RU 486-administered mice. Representative graphs of body weight (A), testicular weight (B), and relative testicular weight (C) among mouse groups on PNDs 4, 10, and 16. Within rows, values with different superscript letters show statistically significant differences (p < 0.05). Values are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of 12 samples per group.

Testicular histology for each mouse groups in PNDs 4, 10, and 16 were shown in Fig. 2A, B, and C, respectively. Histologically, no conspicuous degenerations were observed in the seminiferous epithelium of any subjects. For seminiferous tubule diameter, age-dependent increase was observed in all groups (Fig. 2D). In particular, on PND 16, seminiferous tubule diameter was significantly lower in CORT-administered group compared with other groups. Meanwhile, no significant differences were found among control, RU 486 + CORT-, and RU 486-administered groups. For germinal epithelium height, significant decrease was observed in CORT- and RU 486-administered groups compared with control and RU 486 + CORT-administered groups (Fig. 2E). No significant differences were found among control and RU 486 + CORT-administered groups.

Microscopic sections of testes on PND 4, 10, and 16 in CORT- and/or RU 486-administered mice. Testicular histology of control, CORT-administered, RU 486 + CORT-administered, and RU 486-administered mice on PNDs 4, 10, and 16 (A, B, and C, respectively). Shown are representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained micrographs. Scale bar indicates 50 µm (A) and 100 µm (B and C). Representative graphs of seminiferous tubule diameter and germinal epithelium height among mouse groups on PNDs 4, 10, and 16 (D and E, respectively). Within rows, values with different superscript letters show statistically significant differences (p < 0.05). Values are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of data from 10 animals per group (10 seminiferous tubules or pictures per animal).

At PND 4, no significant change in Sertoli cell number per seminiferous tubule was detected among the all groups, and only faint signals of p27-positive Sertoli cells were detected in the all groups (Figs. 3A and 4). At PND 10, a significant decrease in Sertoli cells was observed in CORT-administered group compared with other groups (Figs. 3B and 4A). The relative p27-positive Sertoli cell number significantly increased in CORT-administered group compared with control and RU 486 + CORT-administered groups (Figs. 3B and 4C). On the other hand, no significant differences in the relative p27-positive Sertoli cell number were found between control and RU 486 + CORT-administered groups. At PND 16, significant decreases in Sertoli cells in CORT-administered group were found compared with control and RU 486 + CORT-administered groups (Figs. 3C and 4A). The relative p27-positive Sertoli cells significantly increased in CORT-administered group compared with control and RU 486 + CORT-administered groups (Figs. 3C and 4C).

Immunohistochemistry for Sertoli cells and p27-positive Sertoli cells on PNDs 4, 10, and 16 in CORT- and/or RU 486-administered mice. Representative micrographs of Sertoli cells, immunostained with anti-GATA-4 and p27 antibodies in testes samples of control (a, e), CORT-administered (b, f), RU 486 + CORT -administered (c, g), and RU 486-administered mice (d, h), respectively, on PND 4 (A), 10 (B), and 16 (C). Merge images for control, CORT-administered, RU 486 + CORT-administered, and RU 486-administered groups are shown in (i), (j), (k), and (l), respectively. Scale bar indicates 50 μm.

Number of Sertoli cells, p27-positive Sertoli cells, and relative p27-positive Sertoli cells on PNDs 4, 10, and 16 in CORT- and/or RU 486-administered mice. Representative graphs of GATA-4-positive cells (A), p27-positive Sertoli cells (B), and relative p27-positive Sertoli cells (C) per seminiferous tubule among mouse groups on PNDs 4, 10, and 16. Values are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M of data from 10 animals per group (10 seminiferous tubules per animal). Within rows, values with different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

On the other hand, in RU 486-administered group, Sertoli cell significantly decreased on PND 16 compared with other groups (Figs. 3C, and 4A). On PND 10, the numbers of p27-positive Sertoli cell and the relative p27-positive Sertoli cell significantly increased compared with control and RU 486 + CORT-administered groups (Figs. 3B and 4B, and 4C). On PND 16, the numbers of p27-positive Sertoli cell and the relative p27-positive Sertoli cell prominently decreased as compared with other groups (Figs. 3C and 4B, and 4C).

Serum inhibin B levels for each mouse groups in PND 16 were shown in Fig. 5. In the present study, it was evaluated to examine Sertoli cell function in our model mice. As shown in Fig. 5, no significant differences in serum inhibin B levels were observed among the all groups.

Serum inhibin B levels on PND 16 in CORT- and/or RU 486-administered mice. Serum inhibin B levels on PND 16 were assessed using ELISA. Values are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M of 12 samples per group.

CORT is a typical glucocorticoid hormone. Our recent study reported that neonatal CORT administration increased p27-positive Sertoli cells followed by decreasing Sertoli cells in mice. However, the mechanism by which neonatal CORT administration caused p27 induction remains unclear. In this study, we found that (1) testicular weight and seminiferous tubule diameter significantly decreased in CORT-administered group compared with other groups on PND 16, on the other hand germinal epithelium heights were significantly lower in CORT- and RU 486-administered groups compared with control and RU 486 + CORT-administered groups (Figs. 1B and 2D, and 2E); 2) neonatal RU 486 administration blocked exogenous corticosterone-induced increase of p27-positive Sertoli cells at PNDs 10 and 16 (Figs. 3 and 4); 3) neonatal RU 486 administration alone caused decreases in Sertoli cells and relative p27-positive Sertoli cells at PND 16 (Figs. 3 and 4).

Previous studies have reported that Sertoli cell proliferation terminates around PND 15 in mice22,23. Moreover, both previous and present data indicate that glucocorticoid signaling is highly important for Sertoli cell proliferation during early life stages. Immunohistochemistry revealed that Sertoli cells decreased by CORT or RU 486 administration during early life stages (Figs. 3 and 4A). These data suggest that both enhancement and attenuation of glucocorticoid signaling during early life stages affects Sertoli cell number. Although excessive CORT administration during early life stages resulted in decreased Sertoli cell numbers in our model mice (Figs. 3 and 4A), it is noted that our findings specifically indicate that RU 486 administration blocks the adverse effects of excessive CORT on Sertoli cell proliferation. We therefore speculate that the appropriate signal induction during the early life stages is required for the normal proliferation and maturation of Sertoli cells.

In the present study, serum inhibin B level did not change among the 4 mouse groups on PND 16 (Fig. 5), although Sertoli cells decreased in CORT- or RU 486- administered groups (Figs. 3 and 4A), suggesting a possibility that secretion of inhibin B from Sertoli cells is virtually increased in CORT- and RU 486-administered mice. Inhibin B level reflects Sertoli cell function or damage24,25, meanwhile it reportedly increases as sexual maturation progresses in rodents26. Several studies showed that puberty onset is accelerated in reproductive system following stresses or CORT administration in early life27,28. We found that CORT administration in early life stages induce p27 expression precociously in Sertoli cells in mice16. Thus, above-mentioned increase of inhibin B secretion in CORT- and RU 486-administered mice could reflect that Sertoli cell development is progressing precociously in these model mice.

p27 is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and a terminal factor for Sertoli cell proliferation at the prepubescent stage17. p27 expression in Sertoli cells is reportedly induced by several hormones, in particular thyroid hormone29. Although our previous study showed that CORT in early life also upregulated p27 levels in Sertoli cells in vivo16, its mechanism remains unclear. Here, our results suggest that the activation of glucocorticoid receptors following CORT administration is involved in the increases in p27-positive Sertoli cells and finally affect the Sertoli cell number in vivo. To obtain more direct verification of the relationship between CORT and p27 induction in Sertoli cells, it may be required to perform in vitro tests of CORT treatments using cultured Sertoli cells. In a future study we therefore plan to treat Sertoli cells isolated from prepubescent mice with CORT and RU 486 and to subsequently analyze their p27 expression levels.

Interestingly, on PND 16, the relative p27-positive Sertoli cells significantly decreased in RU 486-administered mice, meanwhile it had nevertheless increased on PND 10 (Figs. 3B and C). In contrast, in CORT-administered mice, the relative p27-positive Sertoli cells significantly increased until PND 16. p27 induction by CORT may be irreversible while its induction via RU 486 may be reversible reaction in Sertoli cells in vivo; if so, the observed decrease of Sertoli cells in RU 486-administered mice might recover as they grow up. We did not yet evaluate the effects of neonatal RU 486 administration on the testes at post-puberal stages. Additional investigation is therefore required.

Previous studies have reported that CORT regulates the cell cycle in several types of cells. For example, Pinnock et al. reported that CORT administration decreased cellular Ki-67 levels in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus30. On the other hand, CORT is also known to be involved in the apoptosis pathways of Leydig and germ cells31,32. The present results show that the activation of glucocorticoid receptors following neonatal CORT administration increase in p27 level in Sertoli cell, with the resultant decrease of Sertoli cells. Although it is suggested that p27 upregulation by CORT is related to decrease of Sertoli cells, we cannot evaluate proliferative and apoptosis-related activities in Sertoli cells after CORT administration in this study. Evaluation of them would be useful to clarify the effects of neonatal CORT administration on Sertoli cells, and we therefore plan to evaluate Ki-67 and apoptosis signals in the present experimental model.

Overall, the present study is the first to reveal that activation of glucocorticoid receptors following CORT administration in early life stages is involved in the increases in p27-positive Sertoli cells and finally affects Sertoli cell number in vivo. Hazra reported that mice with knockout alleles of glucocorticoid receptors encoded by the gene Grl1 showed decreased number of Sertoli cells33. Additionally, it was reported that the expression of glucocorticoid receptors was observed at PND 20 but not 70 in mice33. Levy et al.. evaluated mRNA transcript levels of glucocorticoid receptor in rat Sertoli cells at PNDs 10, 15, 24, 40, and 60 and confirmed higher mRNA levels on PNDs 10, 15, and 24 relative to 40 and 6034. Such expression and transcriptional pattern of glucocorticoid receptors may support its function in Sertoli cell proliferation, in particular, at early life stage. Meanwhile, inappropriate glucocorticoid induction and glucocorticoid receptor activation in early life stages, in response to ELS, may result in the upregulation of p27 levels and the termination of Sertoli cell proliferation at an earlier developmental stage. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease theory suggests that imbalances in specific environmental factors during early life stages can generate risks for the onset of various illnesses post-birth. In humans, the number of infertile couples has increased over the last few decades. A comprehensive meta-regression analysis has reported a significant decline in human sperm count between 1973 and 201135. Environmental effects during early life, likely ELS, may affect the number and function of Sertoli cells and ultimately lower male fertility. Our previous study reported that exposure to CORT in early life stages caused decreased spermatozoa counts in adult stages. On the other hand, our data suggests the possibility that appropriate RU 486 administration may block the adverse effects with ELS and induced excessive CORT on Sertoli cell proliferation. Decreases in germinal epithelium heights in CORT- and RU 486-administered groups may provide an insight into the importance of glucocorticoid signaling for germ cell proliferation during early life stages. Further studies are required to clarify the mechanisms involved in male reproductive disorders that are accompanied by inappropriate environmental conditions such as ELS and excess glucocorticoid induction.

Ten-week-old male and female mice [Mus musculus, Crl: CD-1 (ICR)] were purchased from Sankyo Lab. All mice were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle at a controlled temperature (24–26 °C). Standard chow (F-2, Funabashi Farm Co., Funabashi, Japan) and water were provided ad libitum. Two weeks later, they were mated. After copulation plugs were found, female mice were separated from male mice. After delivery, CORT and RU 486 administration was performed in neonatal mice. All experiments were approved by the ethics committee of the animal laboratory at Tokyo Medical University (Approval Numbers: R6-067 and R7-094). All experiments performed followed relevant regulations and complied with the ARRIVE guidelines. Animal welfare was monitored in accordance with the institutional and national guidelines for animal welfare (Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments).

CORT and RU 486 administration was performed according as per a protocol previously published by our lab16. Briefly, pregnant dams were first randomly divided into four groups (i.e., 3–4 pregnant dams/group). CORT (27840, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or RU 486 (M8046, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were then dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (049–07213, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and sesame oil (S3547, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). In present study16,20, CORT and RU 486 were subcutaneously injected at doses of 0.36 and 0.0006 mg/kg body weight. Control mice were injected with dimethyl sulfoxide and sesame oil. Vehicle, CORT, RU 486 + CORT, and RU 486 were then administered to mice from PND 1 to 10 (termed control, CORT-administered, RU 486 + CORT-administered, and RU 486-administered mice, respectively). In a previous study, we observed that CORT administration at 0.36 mg/kg body weight from PND 1 to PND 10 resulted in a significant decrease in Sertoli cells on PNDs 10 and 16. In contrast, the p27-positive Sertoli cells significantly increased on PND 10. On the other hand, Jiang et al.. reported that 0.1 µM of RU 486 blocked p27 upregulation with 200 µM CORT treatment.

On PNDs 4, 10, and 16, 4–5 male pups were randomly selected from each litter. Subjects were then deeply anesthetized with medetomidine/midazolam/butorphanol anesthesia, and euthanized following terminal cardiocentesis; testis samples were then collected (12–15 male pups/group). The humane endpoint had been set at 20% body weight loss. In the present study, any mouse did not lead to the humane endpoint.

The removed testes were immediately fixed with Bouin’s solution and embedded in plastic (Technovit 7100; Kulzer & Co., Wehrheim, Germany), without cutting the testes to avoid artificial damage to the testicular tissues. Section (5 μm) were then produced at 25–30-µm intervals and were stained with Gill’s hematoxylin III and 2% eosin Y for observation under a light microscope (BX-51, Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan). Seminiferous tubule diameters and germinal epithelium heights were measured using the ImageJ software version 1.51J8 (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Testis samples collected from each mouse were embedded with Tissue-Tek OCT compound, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C until further examination. The embedded testes were dissected using a cryostat at 5 μm. The resulting sections were fixed with formalin for 10 min at room temperature. For subsequent immunohistochemistry, separate sections were incubated with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-p27 monoclonal antibody (F-8) (sc-1641 AF488, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:100 dilution), which recognizes the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and mouse anti-GATA-4 monoclonal antibody (G-4) (sc-25310 AF594, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:50 dilution), which recognizes a marker of Sertoli cells. Following the overnight reaction, all sections were washed and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (H-1200, Vector Laboratories Ltd.). A total of 10 circular seminiferous tubules were randomly selected from different testicular areas in each animal, to avoid any bias, and one hundred seminiferous tubules were evaluated for each mouse group. The immunoreactive cells were counted using the ImageJ software version 1.51J8.

Serum inhibin B level was measured using ELISA, as described by Miyaso et al.16. Briefly, whole blood (collected at euthanasia by cardiac puncture) was clotted and processed by using standard techniques; the resulting serum samples were collected and stored at − 80 °C until analyses. ELISAs were conducted as per the manufacturer’s protocols [AL-163 (Ansh Labs)].

Statistical analyses comparing the mean values of different mice groups (control, CORT-administered, RU 486 + CORT-administered, and RU 486-administered) were conducted using two-tailed Kruskal–Wallis tests followed by post hoc Steel test, using EZR version 1.36 (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan)36. For all statistical tests, a p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Where appropriate, values were reported as a mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M).

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Thau, L., Gandhi, J., Sharma, S. & Physiology Cortisol. StatPearls [Internet], August 28,. (2023).

Oakley, R. H. & Cidlowski, J. A. The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: new signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 132, 1033–1044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.007 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Das, C., Thraya, M. & Vijayan, M. M. Nongenomic cortisol signaling in fish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 265, 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2018.04.019 (2018).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Zhao, L. et al. Saturated long-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria contribute to enhanced colonic motility in rats. Microbiome 6, 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0492-6 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Trombini, M. et al. Early maternal separation has mild effects on cardiac autonomic balance and heart structure in adult male rats. Stress 15, 457–470. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2011.639414 (2012).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Rosa-Toledo, O. et al. Maternal separation on the ethanol-preferring adult rat liver structure. Ann. Hepatol. 14, 910–918. https://doi.org/10.5604/16652681.1171783 (2015).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Wong, H. L. X. et al. Early life stress disrupts intestinal homeostasis via NGF-TrkA signaling. Nat. Commun. 10, 1745. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09744-3 (2019).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Preidis, G. A. et al. The undernourished neonatal mouse metabolome reveals evidence of liver and biliary dysfunction, inflammation, and oxidative stress. J. Nutr. 144, 273–281. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.113.183731 (2014).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Li, B. et al. Inhibition of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 and activation of receptor 2 protect against colonic injury and promote epithelium repair. Sci. Rep. 7, 46616. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46616 (2017).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Drucker, N. A., Jensen, A. R., Winkel, T., Markel, T. A. & J. P. & Hydrogen sulfide donor GYY4137 acts through endothelial nitric oxide to protect intestine in murine models of necrotizing Enterocolitis and intestinal ischemia. J. Surg. Res. 234, 294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.08.048 (2019).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Sahafi, E., Peeri, M., Hosseini, M. J. & Azarbayjani, M. A. Cardiac oxidative stress following maternal separation stress was mitigated following adolescent voluntary exercise in adult male rat. Physiol. Behav. 183, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.10.022 (2018).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Brummelte, S., Pawluski, J. L. & Galea, L. A. High post-partum levels of corticosterone given to dams influence postnatal hippocampal cell proliferation and behavior of offspring: A model of post-partum stress and possible depression. Horm. Behav. 50, 370–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.04.008 (2006).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Holmes, L. et al. Aberrant epigenomic modulation of glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) in early life stress and major depressive disorder correlation: systematic review and quantitative evidence synthesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16214280 (2019).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Miyaso, H. et al. Neonatal maternal separation causes decreased numbers of Sertoli cell, spermatogenic cells, and sperm in mice. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 31, 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376516.2020.1841865 (2021).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Miyaso, H. et al. Neonatal maternal separation increases the number of p27-positive Sertoli cells in prepuberty. Reprod. Toxicol. 102, 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2021.03.008 (2021).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Miyaso, H. et al. Neonatal corticosterone administration increases p27-positive Sertoli cell number and decreases Sertoli cell number in the testes of mice at prepuberty. Sci. Rep. 12, 19402. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23695-8 (2022).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Holsberger, D. R. & Cooke, P. S. Understanding the role of thyroid hormone in Sertoli cell development: a mechanistic hypothesis. Cell. Tissue Res. 322, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-005-1082-z (2005).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Ausserlechner, M. J., Obexer, P., Böck, G., Geley, S. & Kofler, R. Cyclin D3 and c-MYC control glucocorticoid-induced cell cycle arrest but not apoptosis in lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Cell. Death Differ. 11, 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4401328 (2004).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Kullmann, M. K. et al. The p27-Skp2 axis mediates glucocorticoid-induced cell cycle arrest in T-lymphoma cells. Cell. Cycle. 12, 2625–2635. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.25622 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Jiang, W., Zhu, Z., Bhatia, N., Agarwal, R. & Thompson, H. J. Mechanisms of energy restriction: effects of corticosterone on cell growth, cell cycle machinery, and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 62, 5280–5287 (2002).

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Rogatsky, I., Trowbridge, J. M. & Garabedian, M. J. Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated cell cycle arrest is achieved through distinct cell-specific transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 3181–3193. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.17.6.3181 (1997).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Joyce, K. L., Porcelli, J. & Cooke, P. S. Neonatal goitrogen treatment increases adult testis size and sperm production in the mouse. J. Androl. 14, 448–455 (1993).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Sharpe, R. M., McKinnell, C., Kivlin, C. & Fisher, J. S. Proliferation and functional maturation of Sertoli cells, and their relevance to disorders of testis function in adulthood. Reproduction 125, 769–784. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep.0.1250769 (2003).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Cannarella, R. et al. Molecular insights into Sertoli cell function: how do metabolic disorders in childhood and adolescence affect spermatogonial fate? Nat. Commun. 15, 5582. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49765-1 (2024).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Anawalt, B. D. et al. Serum inhibin B levels reflect Sertoli cell function in normal men and men with testicular dysfunction. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 81, 3341–3345. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.81.9.8784094 (1996).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Buzzard, J. J. et al. Changes in Circulating and testicular levels of inhibin A and B and activin A during postnatal development in the rat. Endocrinology 145, 3532–3541. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2003-1036 (2004).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Biagini, G. & Pich, E. M. Corticosterone administration to rat pups, but not maternal separation, affects sexual maturation and glucocorticoid receptor immunoreactivity in the testis. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 73, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00754-2 (2002).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Belsky, J., Ruttle, P. L., Boyce, W. T., Armstrong, J. M. & Essex, M. J. Early adversity, elevated stress physiology, accelerated sexual maturation, and poor health in females. Dev. Psychol. 51, 816–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000017 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Buzzard, J. J., Wreford, N. G. & Morrison, J. R. Thyroid hormone, retinoic acid, and testosterone suppress proliferation and induce markers of differentiation in cultured rat Sertoli cells. Endocrinology 144, 3722–3731. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2003-0379 (2003).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Pinnock, S. B. et al. Interactions between nitric oxide and corticosterone in the regulation of progenitor cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat. Neuropsychopharmacology 32, 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301245 (2007).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Gao, H. B. et al. Glucocorticoid induces apoptosis in rat Leydig cells. Endocrinology 143, 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.143.1.8604 (2002).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Yazawa, H., Sasagawa, I. & Nakada, T. Apoptosis of testicular germ cells induced by exogenous glucocorticoid in rats. Hum. Reprod. 15, 1917–1920. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/15.9.1917 (2000).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Hazra, R. et al. In vivo actions of the Sertoli cell glucocorticoid receptor. Endocrinology 155, 1120–1130. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2013-1940 (2014).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Levy, F. O. et al. Glucocorticoid receptors and glucocorticoid effects in rat Sertoli cells. Endocrinology 124, 430–436. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-124-1-430 (1989).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Levine, H. et al. Temporal trends in sperm count: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 23, 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmx022 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 48, 452–458. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2012.244 (2013).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Download references

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants (Grant Nos. 22K12417 and 23K11460).

Department of Anatomy, Tokyo Medical University, 6-1-1 Shinjuku, Shinjuku-ku, 160-8402, Tokyo, Japan

Hidenobu Miyaso, Yutaro Natsuyama, Shinichi Kawata, Tomiko Yakura, Zhong-Lian Li, Miyuki Kuramasu, Shota Tanifuji, Xi Wu, Yuki Ogawa & Masahiro Itoh

Center for Basic Medical Research, International University of Health and Welfare, Narita Campus, 4-3 Kozunomori, Narita, 286-8686, Chiba, Japan

Yoshiharu Matsuno

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

PubMed Google Scholar

H.M. designed the research, performed experiments and interpretation of data, and wrote the manuscript. Y.N., S.K., T.Y., M.K., S.T., X.W., Y.O. designed the research and performed experiments and interpretation of data. Z.L. and Y.M. designed the research and wrote the manuscript. M.I designed the research, performed interpretation of data, and wrote the manuscript.

Correspondence to Hidenobu Miyaso.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

Miyaso, H., Natsuyama, Y., Kawata, S. et al. RU 486 blocks inhibitory effect of neonatal corticosterone administration on sertoli cell proliferation in mice. Sci Rep 15, 44372 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28129-9

Download citation

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28129-9

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Advertisement

Scientific Reports (Sci Rep)

ISSN 2045-2322 (online)

© 2026 Springer Nature Limited

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.