Local news organizations can’t be everywhere at once. But even as they slim down, they have column inches and homepages to fill. National wire services can be prohibitively expensive (and less useful as places like the Associated Press reduce their coverage) for small outlets. Services like AP StoryShare or INN’s On the Ground are designed for existing members. Time-strapped local editors don’t want to learn yet another technology or platform only to find it underpopulated and underwhelming.

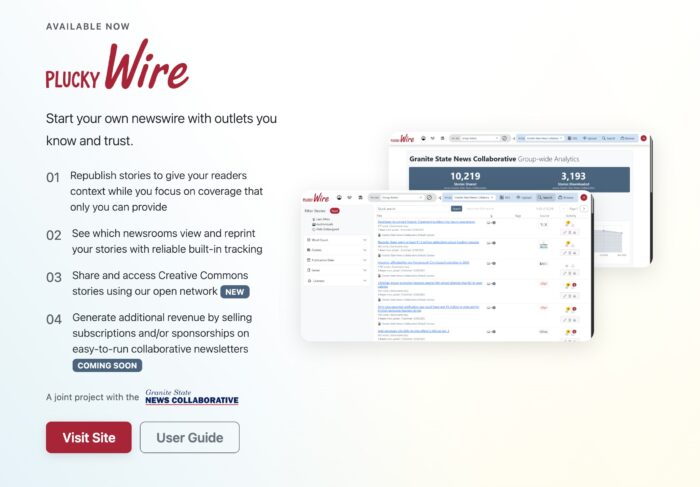

Enter Plucky Wire, a dead-simple website for finding and sharing stories for republication.

Plucky was incubated in an unlikely place: the tiny Granite State News Collaborative in New Hampshire. Its beginnings have given the platform a scrappy sensibility and made it uber-responsive to local news publishers from the start.

Under director Melanie Plenda, the Granite State News Collaborative has forged connections between one-time competitors, introduced new content-sharing partnerships, and launched a press freedom and media literacy campaign across the small New England state. As in many news partnerships, publishers in New Hampshire had been getting by with a patchwork of free products (Google Docs, especially) and a flood of emails (about tracking metrics, corrections, story-specific permissions, and more).

“A sign of success can be when something becomes unusable,” noted Concord Monitor publisher and early Plucky Wire tester Steve Leone. “That became the issue with the way we were sharing. [The collaborative] became pretty central to our news operations.”

Developed by Johnny Bassett, Plucky started from a simple premise: content sharing and collaboration among willing news partners shouldn’t be this hard.

The Plucky platform now has more than 200 publishers, from the couple dozen in the Granite State News Collaborative to major nonprofit news sites like The Conversation. It’s free for news publishers that download fewer than 10 articles per month. Paid memberships start at $15/month for outlets looking to republish more than that.

Plucky Wire was designed and first launched on a budget of about $50,000 — wildly under many of the grant-funded technologies promising to revolutionize local news. Bassett, who works on Plucky along with two part-time developers and a freelance journalist, also credits advancements in AI for being able to do much with (relatively) little. He previously used tools like ChatGPT to teach himself how to code and build one of the largest archives of digital newspapers in the Philippines as part of his doctoral research.

Bassett owns and runs Plucky as a for-profit company, with 20% of profits going back to the Granite State News Collaborative. (Plucky has also received funding from Next Challenge and Muck Rock.) Institutional contracts like those with collaboratives in New Jersey, Vermont, and Washington have provided Plucky with a measure of stability in its earliest days.

“We’re for-profit because we believe that journalism is more independent and resilient when it’s supported by the market, rather than a small number of funders,” the Plucky website explains. “Obviously, we wouldn’t be here without the grants that got us started, but we know that funders don’t want us dependent on them forever. We agree that’s for the best.”

Some examples of how news publishers are using Plucky:

As U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement activities — and subsequent protests — ramped up in the Minneapolis area, Bassett was hearing that local newsrooms far from the Twin Cities were not able to access on-the-ground coverage. He invited a cohort of trusted local newsrooms to share their work on Plucky.

Outlets like Sahan Journal, MinnPost, Minnesota Women’s Press, and the Minnesota Reformer were game and started to share articles, photojournalism, and first-hand accounts on the wire. One recent Plucky newsletter offered 200 photos from the Twin Cities under a Creative Commons license. Others have included press conference write-ups, coverage of official remarks, explainers, opinion content, and more.

Bassett sees the Twin Cities Newswire as an experiment. He’s hopeful, however, about using Plucky to create other “pockets of coverage” in the future. It’s also a way for local outlets to get content from local journalists rather than from national news organizations with fewer local connections.

“Anecdotal reports so far are that people are really excited about it,” Bassett said. “It’s starting to click that it’s sometimes really valuable to have those connections local to local, rather than waiting for news to come down through the food chain.”

News groups can design custom plans on Plucky for their institutional use. In Washington State, this looks like the Evergreen State Newswire.

The local PBS station — long a major provider of statewide Creative Commons content for other local news outlets — has announced plans to cut back on local digital journalism. Jody Brannon, longtime journalist and program manager of the Murrow News Fellowship Program at Washington State University, and Bassett worked to build a new service on Plucky as a partial replacement.

“The cuts [at Cascade PBS] mean outlets like The Leavenworth Echo or The Port Townsend Leader don’t have good access to statewide coverage anymore, because it’s not like The Seattle Times is giving their stuff away for free,” Bassett said. “You have to find some way to piece coverage together now.”

Since launching earlier this month, more than 50 outlets have joined Plucky for the news coverage from 16 fellows producing local journalism for 22 news organizations across the state. Brannon has big dreams for the burgeoning collaboration with Plucky, including adding a public-facing feed and incorporating coverage planning so resource-strapped local news publishers don’t duplicate efforts.

“I’m hoping that, ultimately, Plucky can not only be a distribution channel, but a collaboration one,” Brannon said, “where news organizations are aware of which reporters are working on staple news — anything that you don’t need to send two reporters to — and know that the content would be shared.”

As with others I spoke to, Brannon praised Bassett for listening so attentively to local newsrooms — including some of the smallest newsrooms and newspapers with clunky tech in her cohort.

“I’ve been so delighted with the elegance of Plucky and his responsiveness,” Brannon added. “It’s mind-boggling and exciting.”

Joel Abrams, director of digital strategy for The Conversation, represents another cohort served by Plucky Wire: well-resourced newsrooms with journalism they want to share with new audiences. Abrams said Plucky Wire was addressing some of the longest-standing issues in republication by tackling article discovery, friction in the story-sharing process, and automated corrections.

“One of the challenges for any website like The Conversation that lets anyone syndicate content under a Creative Commons license is that it’s hard for potential republishers to find out about us,” Abrams said. “And for republishers, there’s a real challenge that every website they want to republish from has slightly different ways of doing things.”

“One of the major barriers to republishing I hear from small publishers is that they don’t have the time to do it,” he added, “so if Plucky can make it faster and easier for them, that’s great.”

Many in local and nonprofit news have seen the need for something like Plucky over the years. Abrams himself had applied for grants to build something like it in the past. Heather Bryant, cofounder of Tiny News Collaborative and now an independent consultant, built a similar tool called Project Facet (2015-2019) after she saw newsrooms were using “anywhere from eight to 12 different platforms” for story sharing and coordination.

“One thing I’ve been frustrated about in the journalism industry for many, many years is different offshoots of people tackling the same problem,” Brannon told me. “We diffuse our efforts and all of a sudden we have five platforms.”

“One of the ironic things [about] building collaborative tools is that all of these people agree we need them and then none of them talk to each other,” Bryant agreed.

In the years since Project Facet closed, more and more news organizations have turned from competition to collaboration. That’s partly thanks to efforts like The Center for Cooperative Media and partly because economic forces and the pandemic have forced news organizations’ hands, Bryant said.

Michael Morisy, founder and CEO at MuckRock, has partnered with Plucky Wire. He said helping people who are building tools for journalism has become a major part of MuckRock’s mission.

“Major tech platforms [like Facebook and Google] continue to become more valuable year after year,” he said, “and we don’t give much of our journalism technology the time to evolve and grow and flourish in that same way.”

Morisy pointed to a graveyard of journalism services, platforms, and tools that’ve come before Plucky as a cautionary tale.

“That’s one thing that we’ve seen as really challenging for journalism innovators — all these really promising prototypes that do really, really cool stuff, and they never had more than seven users,” Morisy said. “They never reached a critical mass. They never figured out a sustainability model. We really think that building a more networked future for journalism services and journalism tools can help lift up the field.”

Morisy said he was particularly impressed by Plucky being “designed to support independent newsrooms that don’t have a lot of extra resources, but do often have an outsized impact.”

Bassett, for his part, noted that there are thousands of small newsrooms across the country. They’re critical to their communities and local information ecosystems and yet often overlooked by those building journalism technology. Though individually tiny, taken together, the small newsrooms are a sizable and critical part of local news infrastructure, he pointed out.

“More resources and investment ought to go toward understanding their editorial workflows and their needs, even if each newsroom is itself quite small,” Bassett said.

“If and when collaboration starts to really take off, it won’t be because someone built some whizzy new tech,” he added. “It will be because someone did the much harder work of understanding the demand side of the problem better, leading to a better understanding of small newsrooms’ actual editorial workflows and their readers’ needs.”

Cite this article

CLOSE

MLA

Scire, Sarah. “A scrappy story-sharing tool with local newsroom DNA gains traction.” Nieman Journalism Lab. Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard, 26 Jan. 2026. Web. 28 Jan. 2026.

APA

Scire, S. (2026, Jan. 26). A scrappy story-sharing tool with local newsroom DNA gains traction. Nieman Journalism Lab. Retrieved January 28, 2026, from https://www.niemanlab.org/2026/01/a-scrappy-story-sharing-tool-with-local-newsroom-dna-gains-traction/

Chicago

Scire, Sarah. “A scrappy story-sharing tool with local newsroom DNA gains traction.” Nieman Journalism Lab. Last modified January 26, 2026. Accessed January 28, 2026. https://www.niemanlab.org/2026/01/a-scrappy-story-sharing-tool-with-local-newsroom-dna-gains-traction/.

Wikipedia

{{cite web

| url = https://www.niemanlab.org/2026/01/a-scrappy-story-sharing-tool-with-local-newsroom-dna-gains-traction/

| title = A scrappy story-sharing tool with local newsroom DNA gains traction

| last = Scire

| first = Sarah

| work = [[Nieman Journalism Lab]]

| date = 26 January 2026

| accessdate = 28 January 2026

| ref = {{harvid|Scire|2026}}

}}

To promote and elevate the standards of journalism

Covering thought leadership in journalism

Pushing to the future of journalism

Exploring the art and craft of story

The Nieman Journalism Lab is a collaborative attempt to figure out how quality journalism can survive and thrive in the Internet age.

It’s a project of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University.